Deceptive Luminescence: Indian Legal Lens on Vi-Rex Violet Ray Promises

- Narayani Khanna

- 51 minutes ago

- 6 min read

Introduction

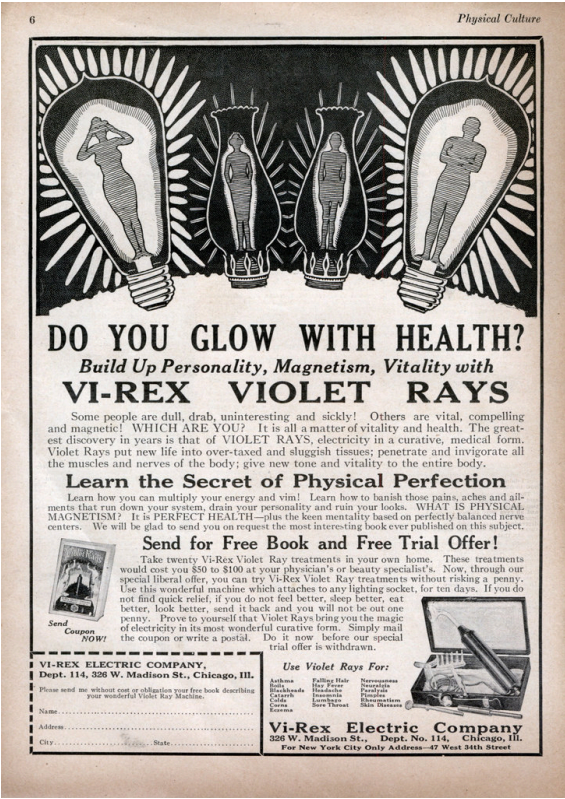

As a young child gazes longingly upon a dazzling, unfamiliar toy, captivated by the promise of novelty, so too did the masses of the early twentieth century marvel at every promise of a scientific wonder. Electricity was an emerging marvel, and such was every illuminated contraption, imbued with an aura of progress and possibility. Against this backdrop, the advertisement for Vi-Rex Violet Rays stands out as a shrewd tactic in exploiting public naïveté. It essentially relies on the idea that the highly intellectual and somewhat incomprehensible modernity could save the bodies, bring the spirits back to life, and give undefeatable strength. However, under this gloss there is a play of manipulative tactics; people, who have been deprived of access to strict medical knowledge, took these 'miraculous' machines in a market full of trust and deceit from the side of the sellers.

The consequences of such deception were not abstract, they were visceral and at times, fatal. The violet ray devices, despite their gleaming promise, left a trail of documented harm. Between the 1940s and 1950s, manufacturers faced numerous lawsuits as evidence mounted of their inefficacy and danger. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (the FDA) launched extensive enforcement actions, seizing hundreds of units and condemning them for misbranding. In a stark 1942 case documented in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a patient died from electrocution while using a violet ray apparatus at home, the device's high voltage discharge passing fatally through the cardiac area. Master Electric, the last American manufacturer of these devices, faced a federal lawsuit in Marion, Indiana in 1951, culminating in the seizure and destruction of their inventory by the FDA. The proceedings revealed a pattern: consumers, trusting in the advertisements' promises of rejuvenation and healing, instead encountered burns, electric shocks, and in the most tragic instances, death. These were not isolated incidents but systemic failures of a market where scientific accountability had been subordinated to commercial gain.

Today, it is absolutely necessary to examine such promises very closely. Consumer protection law is there to protect consumers from precisely these kinds of exploitations. The Indian regulatory environment is a result of multiple layers of reasoning, scientific rigor, and moral determination. It is a system that has been designed to safeguard, educate, and give power to the people. What follows is a dissection of the Vi-Rex Violet Rays advertisement through the cutting lens of Indian Law.

Mirage in the Lamp: ASCI and the Ethics of Illumination

The Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) embodies the watchful eye of ethical advertising. Its Code for Self-Regulation, most recently updated in 2023, acts as the sentry defending consumers from falsehood and exaggeration in commercial communication. At the heart of this regulation lies the imperative: advertisements must speak only what is true, substantiated, and verifiable. In the matter of L'Oreal India Pvt Ltd. v. ASCI (2018), the architecture of deception was exposed when L'Oreal claimed its clay shampoo kept hair "fresh for 72 hours" and its micellar water removed makeup in "one swipe," yet could produce no scientific evaluation to substantiate these promises.

These modern precedents dissect the very strategy used by Vi-Rex. The Vi-Rex Violet Rays advertisement is replete with assertions like tissue rejuvenation, the banishment of aches, and the imparting of vitality that lack empiric foundation. Clauses 1.4 and 1.5 of the ASCI Code require clinical backing for health claims, yet the device in question eschews all scientific validation. Perhaps most egregiously, the ad exploits consumer fears, hinting at the drabness or sickness lurking in those without such devices. It does not merely mislead; it manipulates. In this schema, every misleading testimonial or unsupported promise multiplies the violation, drawing the ad ever further from the realm of ethical advertising.

If such ads were released today, they would be proscribed immediately by ASCI, confirming the pattern set by the L'Oreal case. The moral side of the legal system changes these moments, among other things, to make sure the market is not darkened by deceit but is brightened by truth.

Chasing Shadows: Magic Remedies and the Specter of Quackery

India's legal framework is not blind to the dangers of pseudo-science. The Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act, 1954 is designed to banish the specter of quackery from public discourse. Advertising claims of miraculous cures, absent of scientific foundation, are forbidden under Sections 3 and 4 of the Act.

The Vi-Rex advertisement, invoking concepts like "banishing aches" or attaining "physical perfection," anchors itself to the language of magic remedies, a domain expressly excluded from legitimate commerce. In conflating scientific discovery with fantasy, it seeks to imbue ordinary electrical devices with supernatural potential, a violation both legislative and philosophical. The Act stands as a guardian at the threshold, ensuring that commercial speech does not cross into deceitful sorcery.

The Marketplace of Truth: Consumer Protection and Case Law

With the passage of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, India enshrined the imperative of honesty in advertising as more than an ethical aspiration — it became a statutory command. Section 2(28) defines misleading advertisements in rigorous terms, demanding that every claim be transparent and truthful. The Delhi High Court's reasoning in Horlicks Ltd. v. Zydus Wellness Ltd. (2019) is worth mentioning. In the said case, Zydus claimed that one glass of Complan equalled two glasses of Horlicks in protein content, relying on different serving sizes, but used identical-looking glasses, a fleeting six-second disclaimer, and no clarificatory voiceover in its television commercial. The court held that, despite the underlying data, the overall impression was misleading and disparaging, emphasising that in electronic media the dominant visual message can render fine-print qualifications ineffective. Thus, even partially true claims can amount to "misleading advertisement" when presentation distorts consumer understanding.

Under modern regulations, the Vi-Rex ad with its extravagant promises and indistinct assurances would be condemned, withdrawn, and fined. According to section 21, the Central Consumer Protection Authority is given the authority to take remedial measures, thus safeguarding the market from fraudulent practices and ensuring that fair competition is maintained.

Apparatus of Accountability: Medical Device Regulation and Precedent

In the complex sphere of medical devices, the Medical Device Rules, 2017 demand a higher threshold of scientific and regulatory scrutiny. Devices making therapeutic claims must be registered, clinically validated, and approved by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO). The force of law was made evident in Johnson & Johnson Pvt Ltd. v. Union of India (2020), where breaches of regulatory procedures resulted in product recall and heavy sanctions.

The Vi-Rex Violet Ray Machine is presented in its advertisement as a curative instrument, yet it offers no clinical evidence nor regulatory clearance. Such breaches are not mere technicalities — they are existential flaws in the product's legitimacy. Today, unregistered and unvalidated medical claims invite swift and sure regulatory response, serving as a bulwark against harm.

Conclusion

The systemic vulnerability exposed here is epistemological. Early 20th-century consumers lacked the expertise to evaluate violet ray physics, just as modern buyers cannot independently verify chemical efficacy or protein bioavailability. This information asymmetry creates "consumer disadvantage," where trust becomes the only currency. Contemporary Indian law shifts this burden: advertisers must substantiate before they claim, and regulators must intervene before harm proliferates. The L'Oreal and Horlicks rulings demonstrate that unchecked commercial speech is dangerous and that the difference between truthful comparison and manipulation lies not in the substance, but in the presentation.

All in all, the narrative of the Vi-Rex Violet Rays advertisement is not only an account of a single instrument, but a warning of how dazzling promises can blind reason. Indian consumer protection law acts as a shield and a sword, protecting the public from deceitful commercial talks and thus, putting to rest the sellers of untruths. Court decisions and laws signal a path for ethical trade, making sure that every advertisement is questioned and proven.

The reduction of consumer trust by means of deceptive ads is a social risk that goes beyond the limits of regulation; it lowers the dignity and the intelligence of the consumer. The real essence of Indian advertising law is to protect that dignity, to build trust, and to call for the accountability of those who try to persuade. By means of regulation, precedent, and ethical vigilance, India has created a solid framework that holds business to the highest level, where truth is above all illusions.

Comments